Education becomes pathway to long-term settlement

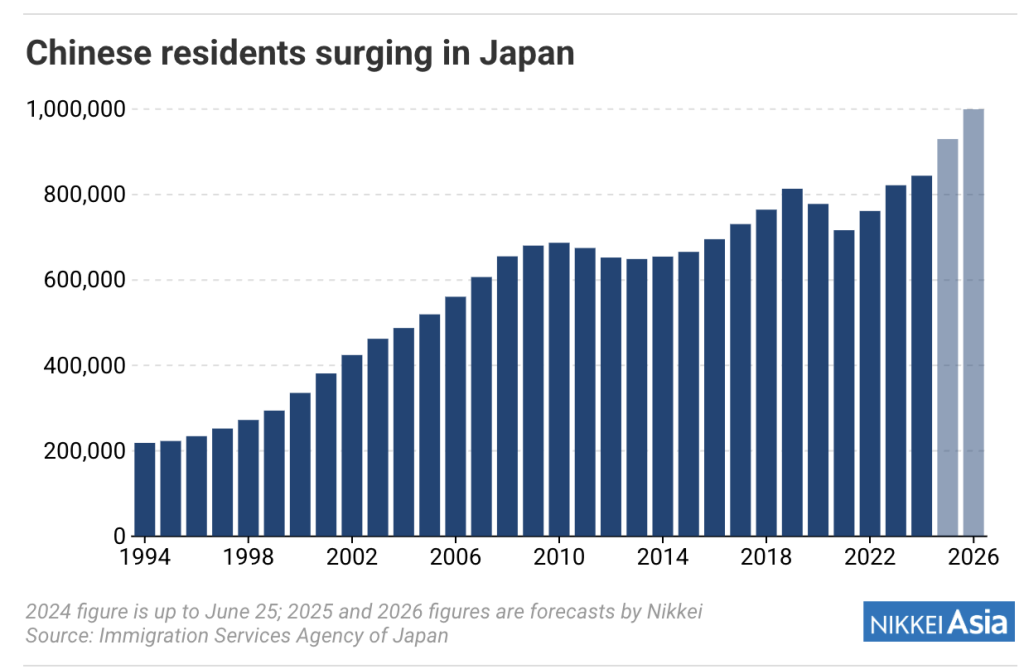

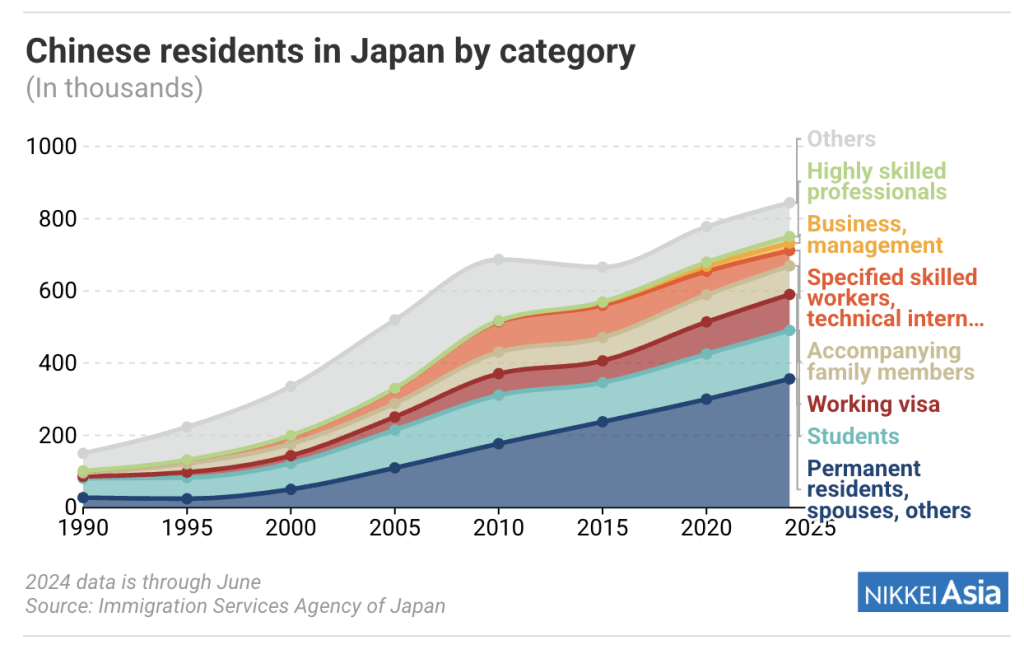

The presence of Chinese migrants in Japan is more prominent than ever before. With the relaxation of visa requirements, migration from China has expanded, offering opportunities not only to the wealthy but also to the middle class. By 2026, the number of Chinese residents in Japan is expected to exceed 1 million.

This increase in Chinese migration is transforming the landscapes, lifestyles, education systems, and cultural traditions of many Japanese cities. It is serving as a catalyst for change, bringing new energy and dynamism to a traditionally static Japan. This series of reports delves into this trend, which has significant implications for the nation’s future. It explores the balance of benefits and challenges while providing a nuanced understanding of its impact.

TOKYO — Li Yalin, a 28-year-old second-year master’s student at the private Kyoto University of the Arts, moved to Japan in 2019 after earning a degree from a university in China. She was studying Japanese at a language school in Tokyo when the COVID-19 pandemic erupted.

Compelled to return to China, she was frustrated, but also determined to come back to Japan after the pandemic. She successfully passed the entrance exam for Kyoto University of the Arts online and now resides in Kyoto. She specializes in character design for video games and other products.

Raised in a middle-class family in Guangzhou in southern China, Li was immersed in Japanese culture from a young age, and was particularly drawn to Japanese games like Pokemon.

«I’ve always admired Japan, and I want to continue living here,» she said. «Life in Japan suits me well. My current dream is to launch the game characters I’ve designed into the market.»

She has secured a position at a game company in Tokyo, where she will start working this spring after graduation. Although she arrived in Japan only recently, she is already exploring the possibility of obtaining permanent residency.

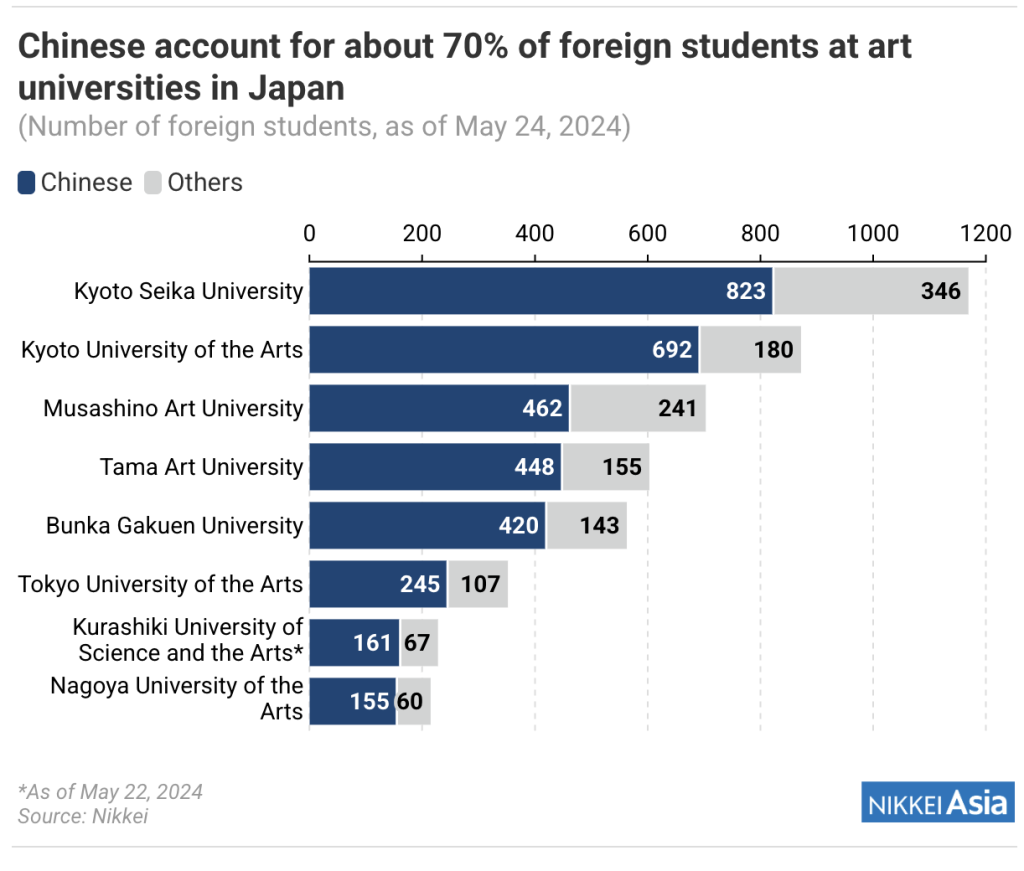

A study by Nikkei shows a significant rise in the number of Chinese students at several leading art universities in Japan. Currently, there are 245 at Tokyo University of the Arts, 462 at Musashino Art University, 448 at Tama Art University, 692 at Kyoto University of the Arts, and 823 at Kyoto Seika University.

Chinese students now constitute approximately 70% of all international students at Japanese art schools.

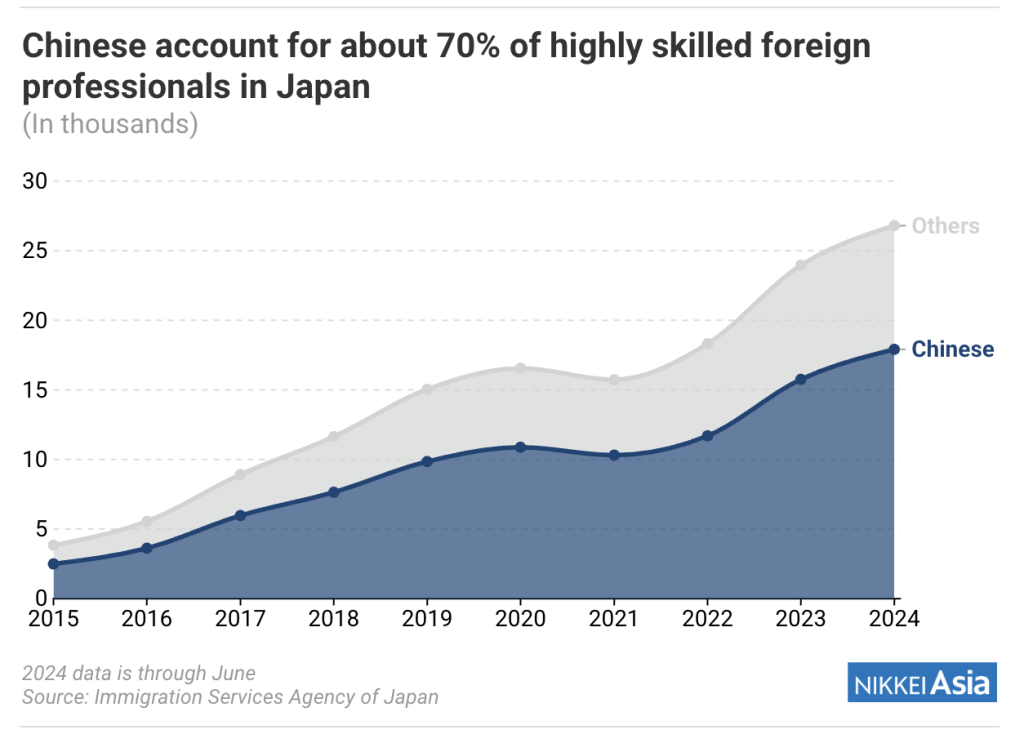

The remarkably high enrollment of Chinese students in Japanese art universities signals a broader trend in Chinese migration. «In fact, this popularity is linked to ‘obtaining permanent residency in Japan,'» explains a migration support agent in Saitama prefecture, just north of Tokyo. Her perspective sheds light on the strategic choices made by Chinese nationals seeking long-term settlement in Japan, using education as a pathway to residency.

The turning point came in 2017 when the Japanese government eased residency requirements. This initiative has been especially advantageous for international students like Li who are pursuing studies in fields such as anime at art colleges.

The 2017 policy reduced the necessary period of residence for permanent residency applications for «highly skilled foreign professionals» from five years to just one to three years.

Additionally, to promote pop culture industries such as anime and design in line with the «Cool Japan» initiative, the government has implemented preferential measures for foreigners working in these sectors, like Li, with a relaxation of the criteria for obtaining a working visa.

Consequently, careers in gaming, anime and design have become quick ways to permanent residency and significantly increased the appeal of art schools among Chinese students.

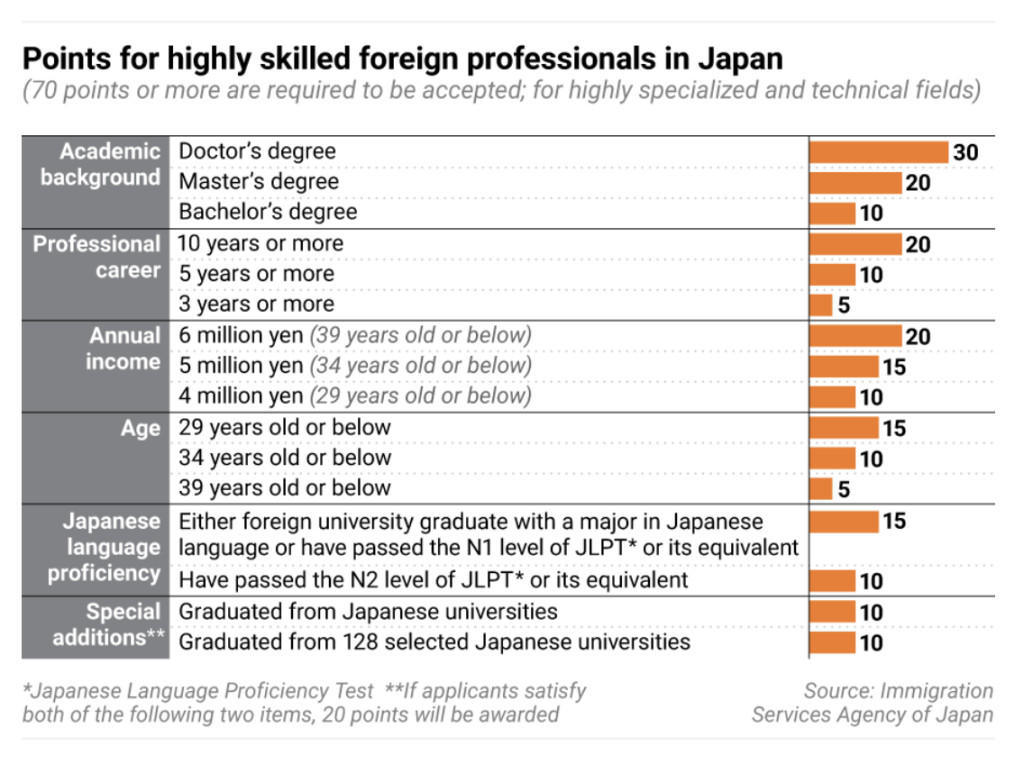

According to an administrative official in Kanagawa prefecture who specializes in visa-related issues, the evaluation criteria for highly skilled foreign professionals are «not very stringent for those who graduate from a Japanese university.»

The assessment process uses a point-based system that accounts for academic degrees, years of work experience, annual income, age, and proficiency in the Japanese language. Achieving a score of 70 points qualifies an individual as a highly skilled foreign professional. Moreover, if an applicant accumulates over 80 points, they become eligible to apply for permanent residency after just one year in Japan.

In Li’s case, if she starts working at a game company in Tokyo this spring, she will soon be able to qualify for permanent residency as a highly skilled foreign professional.

Ren Junying, a 30-year-old native of Hebei province, has already been recognized as a highly skilled foreign professional and currently lives in Tokyo. She completed her doctoral program at Tokyo University of the Arts last spring and is now working as a jewelry designer.

Despite being in the workforce for less than a year, Nin has already achieved a high-skilled foreign professional score of 90. She is actively planning for a future in Japan, stating, «I plan to get married here and have my children educated here.» Nin is also preparing to apply for permanent residency.

Yu Korekawa, director of international research and cooperation at the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, says there is a strong inclination among Chinese coming to Japan for long-term stay with the goal of securing permanent residency. «Japan’s unique system of mass hiring new graduates facilitates job finding and career advancement for international students more efficiently than in other developed countries, including those in Europe and the U.S.,» he said. «This system significantly contributes to the increasing number of individuals obtaining permanent residency.»

As of June 2024, approximately 330,000 Chinese nationals had obtained permanent residency, marking a 40% increase from 2017.

Additionally, obtaining permanent residency benefits spouses, who are automatically granted visas that allow them to work without restrictions. Consequently, the number of «spouses of permanent residents» has significantly risen in recent years, further illustrating the impact of these relaxed policies.

At Coach Academy, a preparatory school for Chinese international students in Tokyo’s Shinjuku district, a group of students practice oil painting. Among them is 25-year-old Yang Kailin, who arrived in Japan in April 2023. After completing her undergraduate degree in China, she decided to pursue postgraduate studies at an art university.

«After graduating, I aim to work for a Japanese toy manufacturer, and, if possible, I would like to live in Japan permanently,» she said.

In 2015, the school introduced an art course specifically for Chinese students. Initially, enrollment was modest, with only about 10 students, but it has since surged to approximately 200. Tetsuro Honma, the head of the art department, noted, «The popularity has now extended to art colleges in regional areas as well.»

Additionally, a staff member at a preparatory school for Chinese students noted a significant shift in motivation: «Recently, I’ve noticed a stronger enthusiasm for studying arts in Japan coming from the parents in China, rather than from the students themselves.» This trend is driven by the fact that if their children graduate from an art college in Japan and qualify as highly skilled foreign professionals, it can also potentially facilitate permanent residency opportunities for their parents.

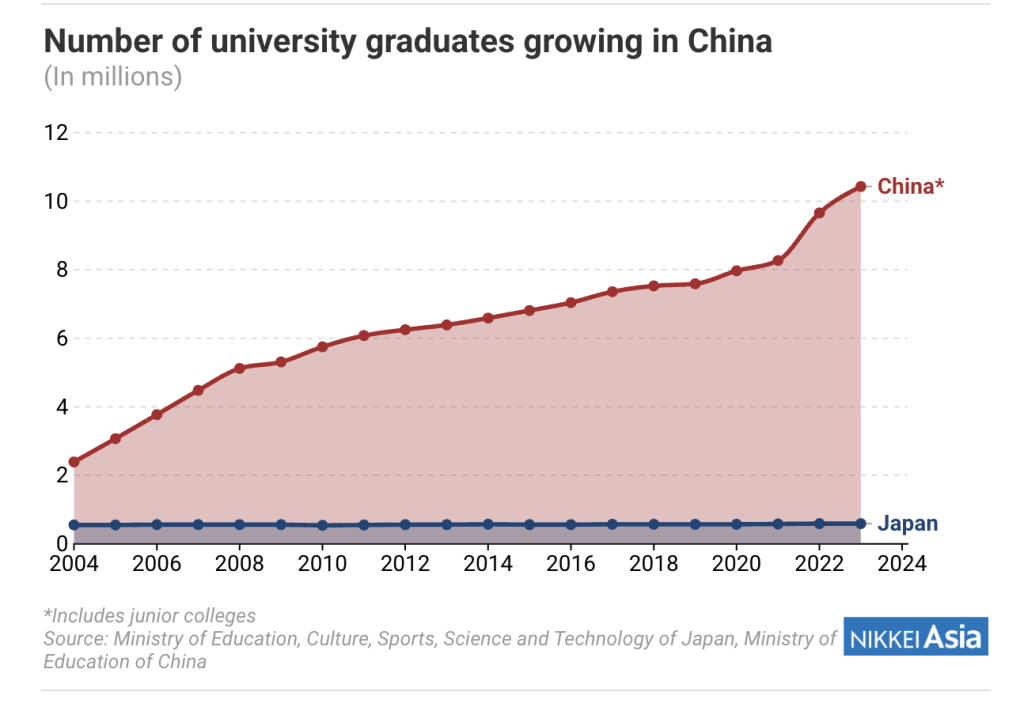

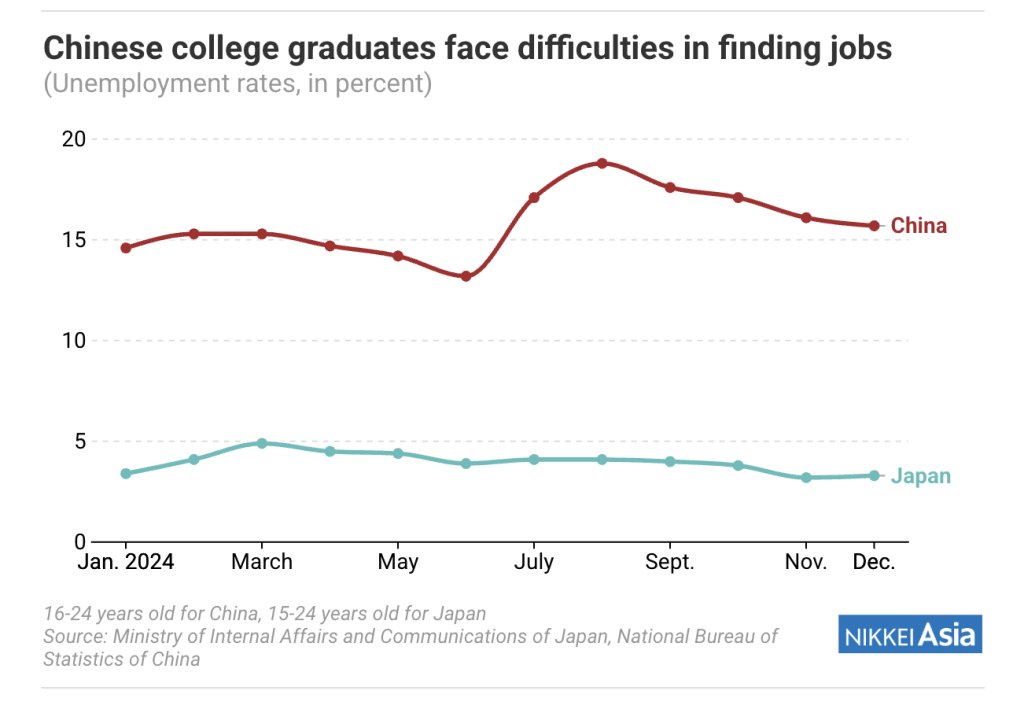

The allure of studying in Japan is reaching beyond art colleges as well. In China, where the economy is sluggish and a sense of stagnation prevails, rising unemployment rates have left many young Chinese searching for new opportunities, and a growing number are considering pathways to Japanese «graduate schools» and residency in Japan.

«A Chinese person who has only graduated from a university in China often faces challenges in being hired by Japanese companies,» said a male Chinese international student. «However, graduating from a Japanese graduate school makes it much easier to secure employment with Japanese companies, and it also facilitates the process of obtaining residency in Japan.»

«Japan is easy to live in, and the health insurance system is particularly appealing,» said Liu Yueye, a 23-year-old female international student. She moved to Japan in July 2023, right after graduating from a university in China, and quickly enrolled in a university preparatory school located in Takadanobaba, a bustling student district in Tokyo.

Liu is currently focused on gaining admission to a national university’s graduate school, which offers lower tuition fees, and plans to reside in Japan after graduation.

«Honestly, I’d be happy with any graduate school in Japan,» said Su Shilong, a 24-year-old from Shanxi province who studies at a Japanese language school as well as a university preparatory school in Tokyo.

Having completed his undergraduate studies in China, Su finds the transition to graduate school in Japan more straightforward. He added, with a smile, «After graduation, I want to find a job and settle down for a peaceful life in Japan.»